Group Dynamics in Meetings

How it can affect decisions

Our previous blog post covered the Task, Maintenance, and Hindering roles that can be observed in group meetings. Let’s follow this up with more information about group dynamics and the impact it has on decision making.

Left to our own devices, most people can make wise decisions, assuming an appropriate level of knowledge to be applied. Put those same people in a group, where peer pressures and herd mentalities may exist, and it becomes important to recognize the pitfalls a previously-wise decision-maker can fall into. Bain & Company is a management consulting firm with the following dynamics to consider:

Ask yourself, are you swayed away from your logic by the influence of others? MeetingSift’s anonymous voting, via smartphone, tablet, or laptop, can help remove the fear of being judged by others when submitting brainstorm ideas or when ranking ideas in terms of importance.

If a group is largely like-minded, there may exist a group confidence that opens the door to hasty decisions since the group sees the collective mind as a majority voice, therefore a reasonable one. The caution is to watch for group actions that readily jump on board a decision without sufficient vetting.

The fear of challenging authority can easily subvert effective brainstorming if no one will speak up in opposition to the “authorities” in the meeting. If you are putting in your two cents in a meeting, ask yourself if you are falling prey to this damaging fear. Again, check out MeetingSift’s anonymous voting.

People acting alone, without fear of judgment, will often act appropriately. If someone is uncertain what to do, and is in the company of others (a meeting), cues from others can have undue influence.

For meetings where the participants don’t, on the whole, know one another, having everyone share some details of themselves, both professional and personal, goes a long way in developing bridges and cultivating interpersonal relationships between people and groups. Nearly always, common ground appears between participants where previously the connections were unknown. Having at least a fundamental sense of the objectives, biases, relative knowledge, and personalities of others in the meeting will lend insight into the group’s ability to work together and, ultimately, achieve the meeting’s success.

Never underestimate the degree to which an individual, or a particular group, may be entrenched in ideologies, in views that can fall into political, economic, and cultural frameworks unbefitting the meeting’s purpose. If there are clearly outliers, such that there is no benefit whatsoever in their attending the meeting, then consider not including them.

John Venn, a nineteenth-century philosopher, created the Venn Diagram where characteristics—the aforementioned objectives, biases, etcetera, in this case—of two or more people (meeting participants, e.g.) are displayed within circles representing each person. Where characteristics overlap (are in agreement) between two or more people, the corresponding shared characteristics are shown within the overlap. Creating a relationship overview can, at a glance, be quite informative as to where the meeting will likely run smoothly, or run into conflicts. Imagine a movie company deciding on which genre of film to produce next. The Executive Producer prefers sci fi, thriller, and comedy. The CFO sees thriller as the most profitable, followed by adventure and horror. Voila! Thriller it is.

Venn diagrams can also be used to show past and present alliances, including possible conflicts of interest, that can shape how group members work with, or against, one another.

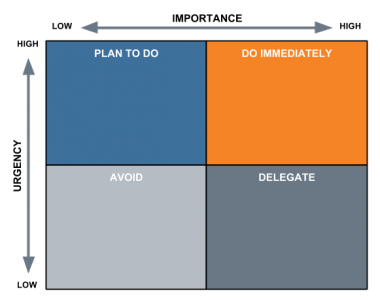

In group dynamics, it may be helpful for the meeting leader to understand where the various stakeholders fit in terms of their importance (high or low) and influence (high or low) regarding the issue(s) at hand. This does not suggest that someone fitting in the low importance/low influence quadrant necessarily has no value in the meeting, since input from this quadrant may be just what tips the scale into arriving at the best solution. Conversely, however, the meeting leader can use this tool in advance of making the invitations in case someone clearly will not contribute to the overall dynamics of the group. MeetingSift offers Quadrants, like the displayed priority matrix, during a meeting to gather participants’ assessment of which tasks are the most, or least, important and urgent in their minds.

In group dynamics, it may be helpful for the meeting leader to understand where the various stakeholders fit in terms of their importance (high or low) and influence (high or low) regarding the issue(s) at hand. This does not suggest that someone fitting in the low importance/low influence quadrant necessarily has no value in the meeting, since input from this quadrant may be just what tips the scale into arriving at the best solution. Conversely, however, the meeting leader can use this tool in advance of making the invitations in case someone clearly will not contribute to the overall dynamics of the group. MeetingSift offers Quadrants, like the displayed priority matrix, during a meeting to gather participants’ assessment of which tasks are the most, or least, important and urgent in their minds.

As the meeting comes to order, the meeting leader can ask the participants to imagine what the meeting’s success would look like, realizing that everyone involved has an interest to that end (though there will be different opinions on how to arrive there). One possible suggestion to the group: “Ask yourself, how can we each achieve the success we are looking for, including helping others to achieve theirs?”

Calling attention to ground rules is an effective way of getting meeting participants to adhere (potentially) to the behaviors and characteristics that assist in moving the meeting forward, and avoiding those that interfere. Go over those rules, with the participants, near the beginning of the meeting (the meeting leader should know in advance whether discussing the list is necessary or not, given the participants). By bringing these rules front and center, modifying as need be, it helps affirm in a fresh light how best to proceed.

From a “Collaboration in Teams” paper, Rutgers Business School, the top positive behaviors and characteristics for collaboration are: being open minded, open to change, cooperating with others, being responsible for one’s work, dependability, being inclusive, solving problems with co-workers, and arguing in a positive manner. Negative behaviors and characteristics include: complaining, being unreliable, not communicating clearly, arguing in a negative manner, and excuses (Sadloch).

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is involved in meetings where stakeholders often represent vastly different interests, as opposed to a company’s internal meetings where participants may not be so polarized. One of the strategies they focus on is Active Listening, as it promotes respect—a key component if different “sides” are to successfully engage with one another. This includes, for example: listen patiently, show that you are listening (nods and smiles help), do not interrupt, do not mindread (i.e., predict what the speaker will say), and withhold judgment as much as possible.

The list and range of ground rules is vast. Here we have mentioned just a few, leaving the more expansive view to the Ground Rules blog.

These can serve a number of purposes. It could be that the meeting has several focus areas (perhaps within marketing, sales, and production). You need to arrive at the heart of an issue in each of these. Divide up the room into separate focus groups—each containing participants whose knowledge and specialties are aligned in solving that particular department’s needs. According to NOAA, market research suggests 10-12 participants as the maximum number, while sociologists suggest no more than 5 or 6. Sensitive topics may do better with a small group, since people may have more depth to explore, more to say. Larger groups can work when comments are limited and perhaps fewer in number.

Meetings can also have breakout groups where the mix of people is not organized but rather simply the meeting breaking out into groups of 3-5 people, perhaps those sitting closest to you. Two benefits come to mind: One is that, in this setting, virtually everyone will have a voice within at least the breakout group—even those who are timid. Another is that it fosters getting to know others in the meeting, which, of course, breaks down barriers that may exist between people.

There’s another option. Let’s say your company is growing and you are thinking of opening a branch in a major city. New York City, Dallas, Los Angeles, and San Francisco come to mind. But which is best? You call a meeting of thirty employees where you will lay out your general view and gather suggestions. Your vision is to break out into four groups that will meet over the next seven days, each tasked with arriving at a ranking among the four cities along with reasoning, reporting back at the next weekly meeting, or perhaps the next day (MeetingSift offers excellent tools for such rankings). Stanford University has a model suggesting breakout group sizes of 5-7 members, within which there are several possible roles assigned, as follows:

If a meeting gets bogged down addressing a particular question/concern, and it is quite apparently not moving forward, try re-framing the question/concern in a different light. By providing a fresh slant, participants who are entrenched in their perspective may be given another way of looking at the issue, allowing them to hopefully relax, or at least review, their steadfast position.

As the size of the group increases, the effort contributed by each member tends to decrease. One recommendation, for problem-solving meetings, is to limit the number of participants to eight (give or take).

Simply stated, the astute meeting leader, along with any meeting support staff, will recognize whether the flow is at it needs to be. Remember, adjustments can be made on the fly. Perhaps a group energizer activity or a short break can be abruptly called, reinvigorating the group and giving those in charge an opportunity to rearrange or redirect as possible. Sometimes it just takes temporarily diverting the meeting from an impending rut, after which the flow can continue.

MeetingSift is designed to improve group decision making in several ways, addressing both with conformity, group polarization, obedience to authority, and bystander effect.

Capturing The Collective Intelligence at Your Meetings

Capturing The Collective Intelligence at Your Meetings